There is nothing new in the realization that the Constitution sometimes insulates the criminality of a few in order to protect the privacy of us all.

— Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia

From the readings and in your opinion, should technology companies implement backdoors in their products for the benefit of the government? Are companies like Apple ethically responsible for protecting the privacy of their users or are they ethically responsible for helping to prevent violent or harmful activities that their platforms may enable? How are these two conflicting goals to be balanced in a world of free-flowing communication and extreme terrorism?

- If you are against government backdoors, how do you response to conerns of national security? Isn’t save lives or protecting our nation worth a little less individual privacy. How do you counter the argument: If you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear?

The debate surrounding Apple and the FBI’s conflict can be clarified by focusing on the two questions it asks:

- Can the US government compel a private corporation to assist through labor of its employees?

- Do US citizens have a right to privacy?

The first question is one concerning the nature of capitalism in the United States and can be approached without needing to engage in matters of privacy or national security. Simply put, the FBI is compelling Apple to build and deploy certain software that is not part of Apple’s business model. Is that OK? The concept of “unreasonable burden” applies to this component of the debate, as many consider this to be an unreasonable burden to place on a private company. This component of the conflict requires additional information on legal precedent on corporate compulsion for me to make a decision, but it does lead into the next question: if such compulsion is OK, in what situations should it be used? The FBI has been very clever in engineering this case: they brandish the phone of a dead murderous ISIS affiliate, and they say, “Why wouldn’t Apple want to get into this phone!?”

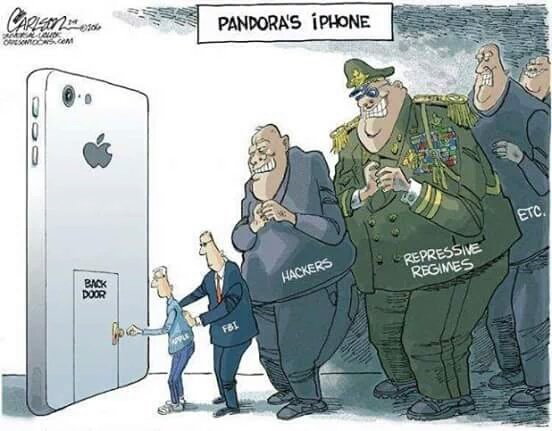

And now we are at the second question. It can be rephrased in several ways: is encryption immoral? Does one have a right to secrets and to privacy? Many do not consider this question to be relevant to the case at at hand because, after all, it’s only one phone. But it’s important for one’s concerns to not be allayed by the FBI’s claim that this less-secure version of iOS will be used only once, because, as Tim Cook says, there is no such guarantee. It’s a slippery slope to recognize the right of the FBI to compromise even one phone, because there is little difference between one phone and two. Additionally, it’s an easy step to ask for further compromises to the components that make iOS secure beyond those currently being requested.

So do we have a right to privacy? It’s essential to consider the encryption technologies at the heart of the conflict (and at the heart of Internet communication in general) for their worth. Encryption allows individuals to communicate and store data securely without fear of theft or interception. Such technologies are typically deployed in the consumer space with the goal of preventing access to personal data by criminals; denying access to the government is a side effect. Without encryption, communications can be easily spied upon, personal data can be stolen, and identities can be compromised. The Internet (and the iPhone) would be a far less useful thing if there were no way to securely transfer data with authority.

So, given the tension just outlined, many come to the conclusion that we can keep encryption, as long as the government gets a backdoor. The problem with a backdoor is that the existence of such a skeleton key, even in the hands of a few, compromises the whole system, because there is no guarantee that the key isn’t being used nefariously. The system will “silently fail” if the key gets out of hand, and the entire foundation of secure Internet communication will be at risk. I understand concerns of national security, but I can’t avoid drawing the parallels to 1984: the dystopian state envisioned by Orwell was undeniably secure, but at what cost?